…

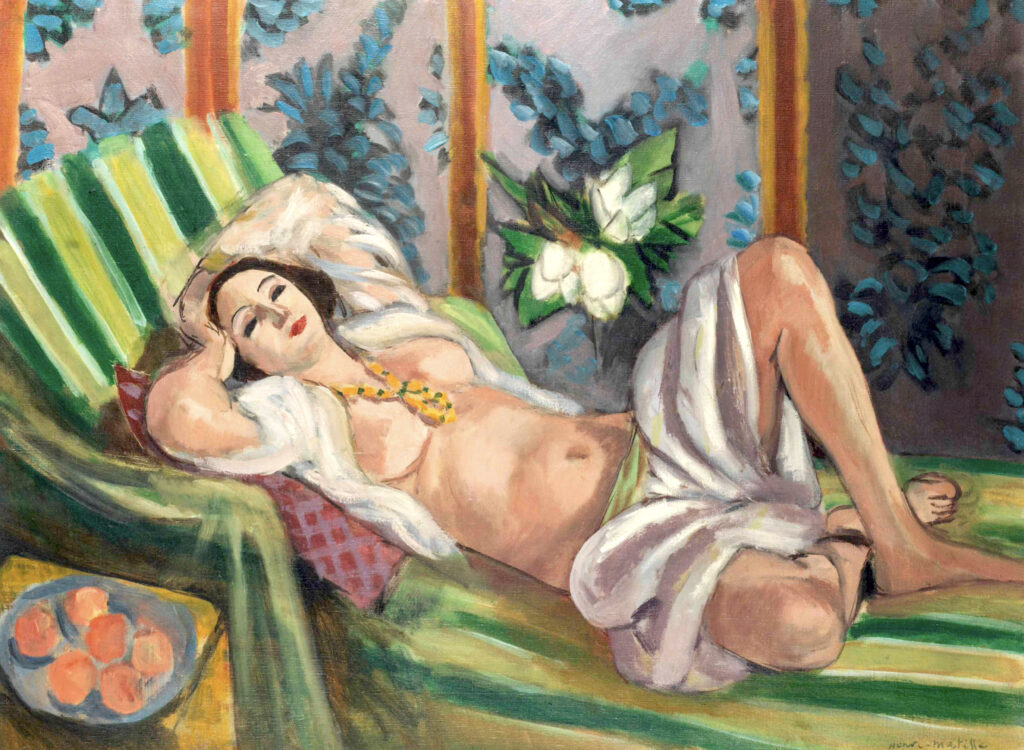

I push open the low front gate to their house. Something happens. As the door opens I register flesh and solidity and a fullness that seems to burst all boundaries.

She is in her late thirties. Her hair is dark black, thick and stiffly coiffed above a broad white forehead; she has heavy black carefully plucked eyebrows above dark brown eyes, a thick sensual nose, and somehow impatient red lips. I think momentarily of Myrtle, Tom Buchanan’s energetic and common mistress in The Great Gatsby.

“I’m Mrs Gold,” she says. Her voice is deep and sonorous and slow, no-nonsense, but she smiles and looks me over. She holds out her hand. Her nails are bright red, her arms ample and full below the short sleeves of the housecoat. Her palm feels big and warm.

She leads me into a plain comfortable living room. Her cork-soled mules (I don’t know that that’s what they are called until much later) tap up and down against her heels as she walks. The toes and backs are open, with just a strap across the arch. She seats herself in the armchair opposite me and leans back, crossing one leg over the other at the knee, dangling one shoe off the front of her raised right foot. Red toenails peek through the front; a white heel emerges smooth and round at the back. She is too ample to be graceful, but she isn’t ungraceful either. I suddenly wonder about her carnal life.

The maid soon brings a small tray with a tea pot, two cups and saucers, milk and sugar and some home-made biscuits. Mrs Gold pours me a cup, and then pours one for herself. She takes a pack of cigarettes off the side table and taps one out and lights it and takes a quick draw.

“Oh my goodness, sorry, I should have asked,” she says as an afterthought. “Do you smoke?”

“Sometimes, yes,” I nod. “I wouldn’t mind one.”

“Of course,” she smiles. She rises and walks towards me with the pack, taps it upside down on the coffee table to shake the cigarettes loose, and proffers the pack. I take one. She offers me her lighter, a small solid slim silver Ronson that looks too angular for her soft fingers.

“It was nice talking,” she says when I say I must go. “Drop in again if you’re near.”

…

Now when I knock on the door, I wait for approaching footsteps and the vague pink shape of the housecoat through the glass. Sometimes the maid answers the door, and, now familiar with me, gives a smile and then shouts up the stairs, Madam, your young man is here …

I think about her. I wonder what to do.

“I married early, you know,” Mrs Gold says to me one day between cigarettes. “Straight out of school. Nowadays girls need time to find themselves – they shouldn’t compete to find a husband so soon.”

“According to Schopenhauer,” I reply stupidly, “all women are natural competitors. They’re like plumbers or shoemakers, all in the same trade.” I explain who Schopenhauer is.

She nods seriously and frowns a little, takes another drag on her cigarette.

“Maybe,” she says slowly, “ … that could be. At least when they’re young. I wonder if I was like that. It’s a little sad, you know, how we set out in life with no idea of what will happen. Or the wrong idea. That hasn’t happened to you yet, you’re lucky … I live differently now from what I expected.”

I like her and I can see she likes me. I take what I can: the flattery of being taken seriously, the surreptitious glances at her incipiently vulnerable body, the beginning-to-get-heavy contours of her face, the full figure and legs, the slow curvaceous walk when she’s relaxed, the index finger impatiently tapping on the cigarette to knock off ash, the sticky red imprint of her lips on the end of the cork filter, a glimpse of a slip between two buttons of the pink housecoat, the way she leans over to touch my arm, intimate and casual when she wants me to refocus my attention on some new question.

Her whole life seems bare of men, and yet … she chooses her clothes and paints her nails to look attractive. Why would anyone do that if they weren’t thinking about men?

On a rainy weekday afternoon during university winter holidays I take a solitary walk through suburban streets to pass her house. The windows upstairs and down are all dark except for the kitchen. I open the gate and walk down to the front door and ring the bell.

She looks worn, not right. “Do you want to come in for a while?”

Tea and cigarettes. She looks distracted as we talk about politics, South Africa, Israel. Suddenly, between puffs, she covers her face and sobs for a moment. I am about to ask what is wrong when she waves her hand up and down in a negative ignore-it sign.

“Don’t ask me anything, please,” she says. She takes a tissue from the table and wipes her eyes.

I look at her. She’s pale. No red lipstick. Her fullness and freshness are gone. I feel deep and sad for her, paternal, and filial too. Shakespeare jumps into my head.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

I have been wanting to touch her for weeks. I walk over to her armchair and stand over her, lean down and stroke her black hair, kiss her forehead. She looks up confusedly.

“What are you doing?” she says sharply, and stands up quickly.

“It came over me,” I say, and back off. “What could I do? I’m sorry you’re sad.”

“My dear! It’s alright! Don’t be upset! I didn’t expect that,” she says.

Later, when I feel I should leave, she walks me to the door.

“Please please don’t be insulted,” she says looking straight at me. “It’s alright. I like talking to you. I’m sorry I’m upset today, I reacted too much.”

She leans forward and kisses me lightly, right on the lips.

…

I return in my car the next day in the late afternoon. She looks a bit agitated when she opens the door.

“Is everything OK?” I ask.

“Thank you for being with me yesterday,” she says. “I have troubles. I cannot talk about them … I read my horoscope today and it said everything will be ok!”

“I’m sure it will,” I say. “Things will work out.”

“Do you really think so?” she asks me, leaning back, entwining her solid legs about each other shyly as though she were a child, looking up at me almost coquettishly.

“Yes I do.”

“Really?”

“Yes. Bad things will pass. I know how it feels sometimes.”

“I’m being silly, I’m sorry. How can you know?” She smiles. “But you’re making me feel better anyway.”

She makes tea.

“I’ve been having such a difficult time for months,” she says quietly while we sip. “Thank you for helping me.”

We talk.

When the time comes I prepare to go to my car. It’s no longer light. She accompanies me outside, which she’s never done before, and waits while I open the car door. She looks sad.

“I can keep you company for a while if you like. Shall I?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says, slowly and softly, assenting with a grave nod, moving her face up and down through such a long vertical arc that, at its nadir, I can see the crown of her head.

I decide to tell the truth.

“I don’t feel like leaving you anyhow,” I say.

She moves forward in the dusk, tilts her head up, and puts her lips against mine. I’m much taller than her.

“Then don’t,” she says, and kisses my mouth and then my cheek.

My heart fills with all the kinds of love I know about. I see her yearning for something I cannot properly understand and I see that she sees my yearning. I kiss her cheek, and she kisses me back.

“Come back inside,” she says with a sigh.